This article was first published in the Daily News 5 years ago (March 11, 2011) under the title 'Gary Sobers may be the future of one-day cricket'. It was written in the context of the Cricket World Cup. Time has passed. Some of the names that were 'names' back then are less relevant now in international cricket. The issues are pretty much the same. And Gary Sobers -- he's still the future of one-day cricket. Oh yes! T-20 cricket too!

The captain of the Zimbabwe cricket team, Elton Chigumbura, won the toss and put Sri Lanka into bat in Thursday’s World Cup match played at the Pallekele Stadium. He offered the logic that his team was spin-heavy and worried that if he opted to bat first, the spinners would struggle with a dew-soaked ball. What this underlines, apart from the importance of reading pitch and conditions, is how important and arduous the task of team selection can be.

It’s not easy picking the right combination of openers, which set of batsmen make the best available middle-order, the number of bowlers to use, the appropriate mix of pace and spin, whether to go with a batting all-rounder or a bowling one etc. Some teams are packed with all-rounders.

The problem is that only a very few all-rounders can be called specialists with bat or ball. Teams need to have specialists if they want to be consistently good. Part timers will deliver but only on occasion and one has to be a big time gambler to believe that one or more of them would invariably come up with a potentially match-winning performance each time the team takes the field.

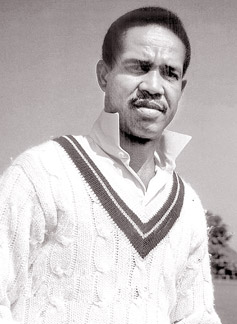

Gary Sobers |

The dew-factor comes into play in day-night matches. The problem in the case of dew-factored matches is that no one can predict the outcome of the toss. Teams don’t know if they’ll bat first or not.

To add to the complexity, there’s a widely held notion that chasing under lights is tough. So someone like Chigumbura has to juggle the issue spinners not being able to grip with that of the supposed difficulty of batting second under lights. In general, the relevant strengths of the team are key in deciding what to do in the event a captain wins a toss. The strengths and weaknesses of the opposition are also considered, naturally but the human resources at hand are far more compelling in decision-making.

In this context flexibility must be considered an edge. The key word is ‘options’, not just at the point of team-selection, but on the field itself. Teams that can shuffle the batting order can adjust better to match-situation. They can move someone up the order to respond to a big total by the opponent, to hold things together in the event of losing quick wickets or take the opposition out of the game with some big hitting if the right foundation has been built by the top order.

It’s the same with the bowling attack. Variety and multiple-options come handy if the wicket doesn’t play as expected. Sri Lanka’s success in the mid to late nineties is often attributed to a solid batting lineup. The openers were explosive. They were followed by solid stroke-makers and a bunch of utility players down the order who could be relied on for some lusty hitting or even a patient fifty to post a respectable score if the top order failed. The same was true of the bowling attack. The stand-out names were Vaas and Murali but Sanath, Aravinda, Kumar Dharmasena and Upul Chandana could be depended on to contain batsman or get a breakthrough.

On the other hand, there is very little that a captain can do if after opting for a pace-heavy attack suddenly finds that the wicket is taking spin. In the Zimbabwe match the Sri Lankan pace attack was comfortably handled by Taylor and Chakabva. Murali delivered as he usually does when he has to, but it was a part-time spinner, Dilshan, who really shone, underlining once again the importance of all-rounders. Sri Lanka went in with two genuine fast bowlers, Malinga and Kulasekera and it was expected that Matthews and Thisara Perera would be called on to bowl full quotas. That’s ‘pace-heavy’. Dilshan put his hand up, yes, but this was Zimbabwe and not Australia and moreover, one really cannot expect him to do this every match or even once every three games.

Gary Sobers

Full name : Sir Garfield

St Aubrun Sobers

Born : July 28, 1936 (age 74)

No of tests : 93

No of runs : 8,032

Batting average : 57.78

No of wickets : 235

Bowling average : 34.03

|

Dilshan is no doubt an exceptional talent. He can bat anywhere in the order, is a brilliant fielder, can be counted on to step up to the bowling crease (111 wickets in 199 ODIs and an economy rate of 4.74 is impressive for a part-time bowler) and can even keep wickets. Sanath never kept wickets, but he was as or more impressive with bat and ball and in the field as well. Dilshan had big shoes to fill and he’s shown that he’s a neat fit. There is no doubt that teams with Dilshans and Sanaths have an edge, but it is increasingly apparent that every team has a Dilshan or at least someone who can be one 8 times out of 10. Pakistan has Afridi, India has Yuvraj, South Africa has Kallis, New Zealand has Vettori and so on. What no team has today but which every captain would love to have is a Gary Sobers.

He was the finest all-rounder in modern cricket. He was an elegant stroke-maker who could also butcher any attack. He was a brilliant fielder in any position. Most importantly, his versatility with the ball remains unmatched, 37 years after he played his last Test. Sobers could bowl two styles of spin (left-arm orthodox and wrist spin) and was a fine fast-medium opening bowler. He was the kind of all-rounder who could not be called ‘a bowling all-rounder’ or a ‘batting all-rounder’. He could not be called ‘pacie’ or ‘spinner’. He could not be called ‘paceman who can bowl spin’ or ‘spinner who can bowl fast’. That’s versatility.

All we can say is that not a single captain leading a team in this World Cup would have hesitated in including his name regardless of opponent, stage of the tournament, condition of pitch or whether or not it was a day-night match.

As cricket gets more competitive, conditions harder to predict and on-field situations ever more complex in ODIs with power-plays augmenting the number of possible scenarios, a Sobers in the team can make a huge difference to team strength. To illustrate the point, Shahid Afridi is officially a spinner but can bowl fast-medium if he wants to.

I am not sure if Dilshan can wear a medium-pacer’s hat, but perhaps Matthews or Thissara Perera can do some slow tweaking on occasion. Kumar Sangakkara’s range of options would immediately be enhanced and this without having to worry about dropping a batsman or a paceman to accommodate an extra spinner. For the record, Muttiah Muralidharan, before he became a spinner, was a fast-medium bowler at St. Anthony’s College, Katugastota.

While there is a lot of truth in the adage ‘Jack of all trades, master of none’ and while admitting that cricketers like Sobers are a rarity, cricket authorities the world over might want to think about designing programs that increase the chance of a) discovering a Sobers and b) nurturing those who have the potential to emulate the great man.

This article was first published in the Daily News on March 12, 2011.

malindasenevi@gmail.com

0 comments:

Post a Comment