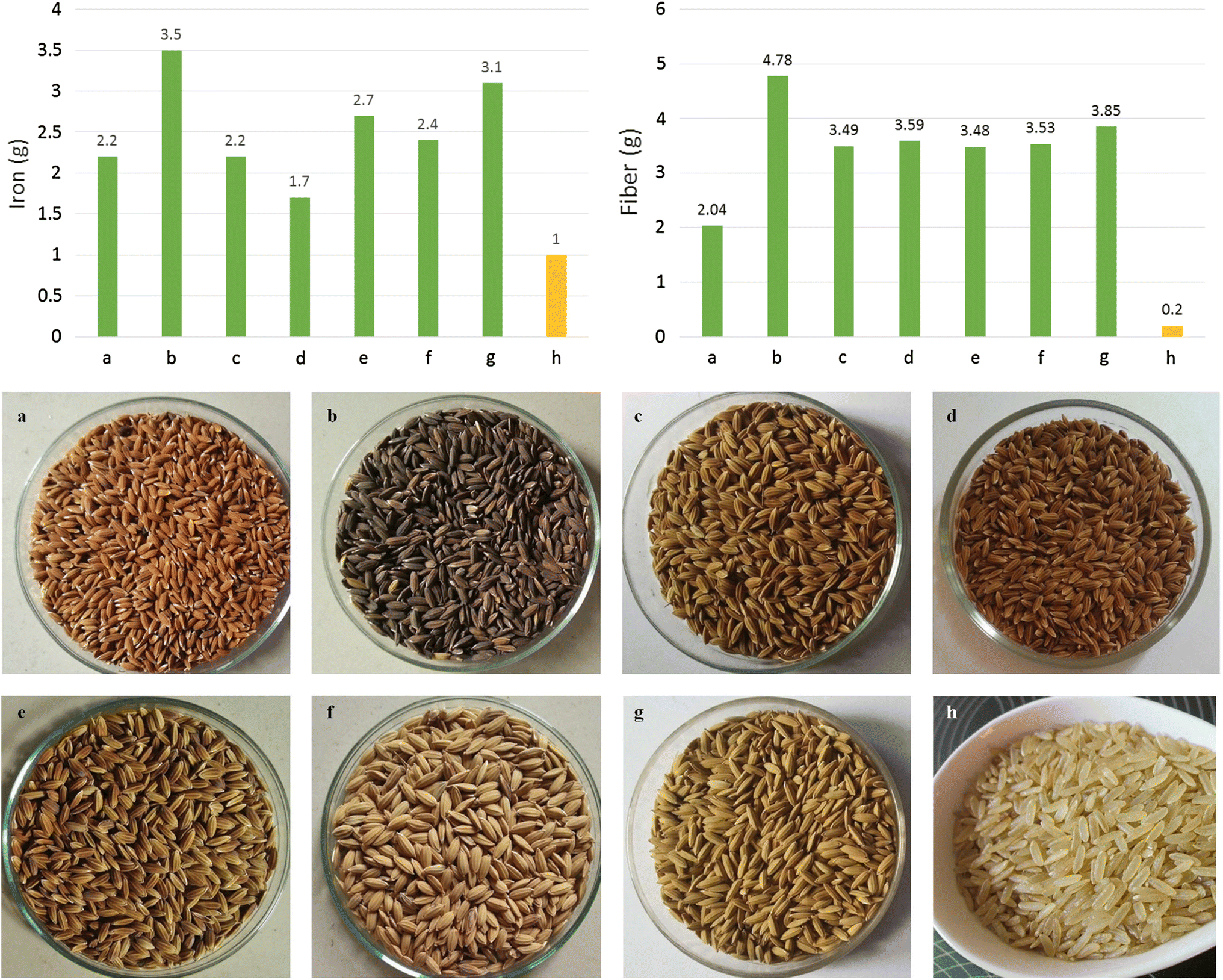

Comparative iron and fiber content of traditional Sri Lankan rice varieties (Oryza sativa): a fragrant rice (Suwandel); b dark rice (Kalu heenati); c red rice (Kurulutuda); d red rice (Madathavalu); e red rice (Pachchaperuma’l); f Pokkali rice; g Sudu heenati rice; h white rice (milled). Values are expressed per 100 g of raw rice. For local varieties, values were measured after dehulling.

Sources: Local varieties: BFN Sri Lanka, White rice (H): Longvah et al. 2017. Photo credit: BFN Project/S. Landersz

Seed. Technically it refers to 'the unit of reproduction of a flowering plant, capable of developing into another such plant.’ As such, it has immense metaphoric applications. Just google ‘seed + quotes’ and you’ll get dozens. By and large it has positive connotations, after all anything that can generate ‘more of the same’ does sound rich. ‘Seed’ is a wholesome word because it is all about renewal, regeneration.

There are of course negative uses, a flip that tells if you will, for example ‘seeds of destruction.’ There are wicked seeds, if you will. They could come in the form of ill-temper or fault line or in general some structural mismatch or error that sooner or later bring down edifices. These ‘edifices’ could be communities or nations, corporations or agreements. Anything, really. In fact, one could even argue that given human fallibility, all systems do contain ‘seeds of destruction,’ only some are containable and some resilient beyond control.

Now there are seeds and seeds, wholesome and otherwise. And then there are seeds that are designed to destroy and those designed to die just in order to generate dependency on the one hand and profit on the other. Pernicious seeds. Those who believe agriculture is about inputs and outputs but not about politics and ideology are a bit naive. Much of it has little to do with feeding a population; but is mostly about securing and controlling markets just for the sustainable development of bank balances of a few.

It is for this reason that any agricultural policy has to take into account the overall realities made of structures and processes which include the privileging of certain ‘sciences’ over others and indeed the marketing of certain theories and dismissal of others. A ‘theory’ which focuses on a segment, tosses out the imponderables or those factors that cannot be quantified or categorized, and is deliberately made to strut around as ‘last word’ on this or that is not theory, really. It’s not science either. Such theories and sciences abound and if the world is even a tad more unhappy these things are in part responsible.

All beings need nourishment. All beings need to secure nourishment. Organised societies, especially marked by increasing complexities, have come a long way from subsistence agriculture. Few if at all produce everything they consume. This is why, in Agriculture, for example, there are producers and consumers, broadly speaking.

And they have habits, some acquired and some induced. So it is with plants and that is why agriculture is different from ‘gathering.’ And that’s where certain practices are wholesome and others are pernicious.

Now one can argue that the entire chemical industry pertaining to agriculture was built on and grew with nothing but goodwill and benevolent intent. That’s a bit naive and that’s what the principal beneficiaries, i.e. the chemical input makers, would like people to believe. The truth is that species can be made to be addicted, but unlike in the case of human beings when it comes to crops it begins at birth. With the seed.

If there’s a seed which pushes out from the earth and needs particular kinds of nourishment to survive and thrive, then written into the process are the relevant inputs. If it is engineered to attract certain kinds of pests, then certain kinds of pesticides need to be sprayed. Same with weeds and fungi. And if natural predators or other entities that are capable of combating weeds, pests and fungi are killed in the process, all the better. All the better for those who manufacture and peddle these chemical inputs.

This is why, any process that seeks to push things towards natural farming, cannot succeed if the entire process is not reviewed, from A to Z, beginning (seeds) to end (food cultures) and within the larger framework of the political economy associated with agriculture. So this is also about food security and, more importantly, food sovereignty.

If the seeds are pernicious, no amount of effort to replace one of the chemical inputs with natural alternatives can deliver the goods. The answer is obviously in seed replacement. This requires a review of current seed policy and a kriyaanvithaya, so to speak, of propagating and promoting wholesome seeds.

Ah, but what about yields? Won’t they drop? Yes, such questions are asked and they are valid. Ah, but why talk of yield density but not density? Ah, such questions are not asked and that’s no accident.

Consider nutrition density. Compare hybrids with traditional varieties. The protein content of the latter is much higher than the former. It’s the same when it comes to iron. Altogether, more healthy. And get this: you don’t need to consume as much to fill your stomach. Indeed, you’ll probably get hungry much quicker if you ate ‘hybrid rice’ as opposed to varieties such as pachchaperumal, kalu baala vee, kalu or rathu heeneti, gonabaaru, madathavaalu or suvandel.

But who eats this stuff? And do we have enough? Valid questions. We don’t eat ‘that stuff’ because a) that stuff is not being grown, and b) we have got addicted to ‘that other stuff.’ Not an accidental turn of events though. We bought the green revolution lie and consumed it, smacking our lips, for decades. We persuaded our tastes to be altered and our minds to be warped — we consumed the propaganda that made us consume the unwholesome. No one promoted the traditional varieties. The half-truth (which is a half-lie) of yield density was drummed into the heads of economists and the general public. We learned to forget nutrition. We thought ‘taste’ was what counted, not nutrition. So yes, there’s a food culture ‘Z’ that needs to be addressed as well.

It starts with the ‘A’ that is ‘seed’. The President has boldly sought to turn things around and rescue citizen and nation from this pernicious dependency on chemicals. If this courageous move is to deliver intended results, then now is the time to sort out the seed-problem. Farmers have to be encouraged to grow traditional varieties (and not just of rice) and they need to be assured that the yields will be purchased, held and used to cultivate a greater extent of land. It is pertinent to point out that traditional seeds were purchased by proxies of seed manufacturers so there would be none to compete with hybrid alternatives (yes, again, not just rice).

The hybrid is a player in a game that is slanted against food security and dents food sovereignty. This needs to be understood. Obviously there are many elements to this struggle such as production of alternatives to chemical inputs, testing, certification etc. Food cultures, as mentioned, need to be addressed. Yes, there’s a lot to do if we are to go from a different A to a different Z. Let us repeat: it begins with A. Seeds.

Sri Lanka needs to be re-grained. That’s not negotiable in this struggle.

malindasenevi@gmail.com

[Malinda Seneviratne is the Director/CEO of the Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training Institute. These are his personal views.]

1 comments:

හොඳම හාල තමයි ගොඩ නැත්නම් ඇල් වී හා තන වී.හේන් වල වපුරපු ඒවා. බිරිතානියන්ගේ වතු ආර්තිකය අපේ හේන් කැලෑ වතුකලා ඉන්දියන් කාරයොත් එක්ක එකතු වෙලා. ඉන්දියන් කාරයො බුරුමයෙ වී වවල අපිටයි වතුවල උන්ටයි හාල් ගෙනත් නිකන් වගේ දුන්න. අපේ වී වගාවේ අවසානය. නිදහසින් පස්සෙ වැඩිජනගහනයකට කන්න දෙන්නයි මෙරට ආහාර ස්ව රැකීමට හරිත විප්ලවයට එක්වුනා. කුනුපොහොර කෙලියෙන් අන්තිමට කුනු පොහොර තමයි කන්න වෙන්නෙ

Post a Comment