Politics is about claims and counter-claims. It is about profit-seeking through exaggeration and pooh-poohing. It is also about wild extrapolation of conclusions wrought in echo-chambers. It is as much about deception as it is about self-deception. Perhaps an example would illustrate the point.

Way back in 2010, a few weeks before the presidential election, a diehard UNP supporter said, ‘this time Mahinda is finished, you wait and see!’ I asked, ‘on what basis do you say this?’ ‘Everyone is saying it,’ was the emphatic response. I asked, ‘All these people who told you that Mahinda is finished, who did they vote for in 2005?’ The answer was quick, firm and once again emphatic: ‘Ranil!’ Emphatic conclusion was tested and proven false a few weeks later.

Elections. That’s what gives finality to contending perceptions of general drift. Elections, courtesy certain elements in the 19th Amendment retained in the 20th, cannot be called this early on whim but only under special circumstances.

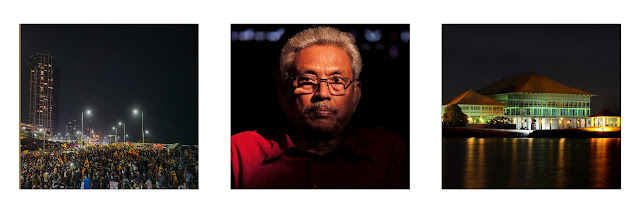

That said, there are often signs which can’t be easily dismissed simply on account of inability to ascertain public sentiment perfectly. Dissatisfaction is too stark to be ignored. Widespread and open dissent is not just visible but it is continuous. The current quibbling among parliamentarians and political parties, the call for resignation and interim arrangements as well as constitutional amendment clearly indicates acknowledgement of a crisis.

It was all put in a nutshell thus by a university professor: ‘The size of the barricade is proportionate to the magnitude of fear of the person hiding behind [it]. These are unmistakable signs that the message of the “struggle” is more powerful than the bombs and bullets of ruthless terrorists.’

Who and what are behind the barricades is a question that has an easy as well as a complex answer. ‘Obviously those who are being targeted by the protestors,’ would be one. The objection however is not just to a single individual — there’s rejection of not just the ruling party but all parties, party politics and the entire political system and culture. These however get less play; after all a catch-all target is easy to aim at and makes for easier mobilisation of objectors. Regardless, legitimacy has not only been questioned, it has been rejected outright.

The illegitimate, common sense demands, should make way for the legitimate. That’s where we hit a wall. Is there any individual or collective that can claim the legitimacy mantle exclusively? Let’s consider the claimants or rather those considered by some to be pretenders to the political throne.

Is there any individual in Parliament who can claim that he or she has a greater claim to the big seat than anyone else, incumbent included? Well, the person who polled the highest number of preferential votes would still only have the results of a district to show. A party? Which? Even if we put aside the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP or ‘Pohottuwa’) on account of, say, ‘visible illegitimacy,’ can the Samagi Jana Balavegaya (SJB), Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) or any other party represented in Parliament claim to have the confidence of the people to seize power? No.

Perhaps this is why there’s some traction for the proposal for an all-party interim cabinet or a cabinet made of experts in key areas brought in through national lists emptied voluntarily by the relevant political parties who would, ‘in the interim,’ back them to take firm if difficult and unpopular decisions to put the country back on track. Again, though, legitimacy could be questioned. It is of course obtainable, theoretically at least, only upon delivering tangible results, economic in the first instance and political reforms later, perhaps.

Legitimacy is also an issue on the other side of the barricades. In the political ‘overall’ of practice the question of precedence can be raised. If, for example, incumbent politicians have to ‘go home’ each and every time they are corralled by objectors, the same logic could be applied for calling bosses of all kinds to resign: students could hoof out teachers, teachers could ‘send home’ principles, congregations could throw out priests etc., etc. Protesting is a right. It is legitimate. Neither is it illegal for calling someone or some political order to question and demanding resignation. This is normal: one asks for much and settles for less.

On the other hand, if one is intransigent on the ‘much’ then one would probably have to raise legitimacy to a higher level. An eclectic group gathered simply on account of commonality of a singular objective (resignation of incumbent, say) may frighten someone or some political entity to submission, but in this case, given the legitimacy deficiency of would-be successors, the very same group is likely to provoke new barricades by the newly barricaded. That’s unless they are just pawns of someone or some group that seeks to prey on uncertainties and displeasure to further narrow interests.

I prefer to be optimistic. I prefer not to see conspiracy at every turn. It would be presumptuous to advise the protestors. I would not say, for example, ‘give us clarity on leadership and programme.’ After all, sometimes, the barricaded want leaders identified. ‘Sitting ducks’ thereafter. I prefer for them to figure out what's what, what can be and how to get to wherever they believe they should go. However, if legitimacy is something they have at heart, then they would do well to obtain it, one way or another. As of now, legitimacy is contained within the ‘articulator of dissent’ parameters. Splendid in and of itself. Necessary too, obviously. Not sufficient, I would say.

malindadocs@gmail.com.

[Malinda Seneviratne is the Director/CEO of the Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training Institute. These are his personal views.]

0 comments:

Post a Comment